The bacterium that scorched the olive groves of southern Europe has not reached Tunisia. But a changing climate, insect vectors and an overly porous plant trade are tightening the noose – with the fate of a million people hanging in the balance.

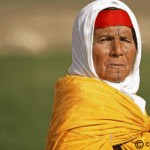

At dawn in Sfax, silver canopies ripple over the stone terraces. An olive grower inspects the young shoots for the tiniest betrayals: curling tips, dulling sap, a bronze border at the edge of a leaf. He tracks down an absence: the invisible bacterium that has already deformed landscapes all around the Mediterranean. Tunisia is still free of Xylella fastidiosa. But season after season, the roll of the dice seems less forgiving.

The situation

In August 2025, the European Commission still classifies Tunisia among the countries officially recognized as Xylella-free under the EU plant health regime, a hard-fought status. Yet the outbreaks detected in European regions since 2013, combined with increasing vector pressure, leave little margin for error.

What is Xylella and why is it so difficult to stop?

Xylella fastidiosa is a xylem bacterium transmitted by leafhoppers (notably the ” foamhoppers “, family Aphrophoridae) and other biting-sucking hemipterans. It can infect hundreds of plant species – olive, almond, vine, citrus – and there is no curative treatment once the tree has been affected. The answer lies in one word: speed; detect, contain, uproot, compensate.

Why Tunisia is exposed

Geography and climate play their part. Sicily and other infected areas are only a short distance from the sea; the semi-arid belts of the interior offer favorable conditions for vectors in spring and early summer. Then there’s trade: legal or “grey” flows of plants, cuttings and grafts that can allow pathogens to slip through the cracks.

Fieldwork in Tunisian orchards has already mapped the risk. A multi-region survey (2018-2021) trapped 3,758 Aphrophoridae out of 9,702 insects sampled, with Philaenus tesselatus and Neophilaenus campestrisdominant on olive trees and nearby wild hosts – an ecology ripe for dispersal should the bacterium arrive.

Strong but not invincible defences

Since 2015, Tunisia has deployed a national surveillance network under the aegis of the General Directorate of Plant Health (DGSV)supported by PCR diagnostics at theINRAT and theOlive Tree Institute. Inspectors and extension agents were trained in rapid sampling and reporting; international partners (FAO, CIHEAM, EPPO) supported tabletop and field exercises. In May 2025, EPPO and NEPPO conducted a three-day workshop in Hammamet to test full-scale Xylella emergency protocols. But loopholes remain. Pockets of smallholders still escape coverage; human and logistical resources are stretched over an immense olive-growing territory; awareness campaigns remain uneven across regions. Illegal or poorly certified plant material remains a backdoor. So many seams that a rapid plant epidemic knows how to exploit.

What’s at stake

The olive tree is the economic backbone and cultural emblem of Tunisia: 1.8 million hectares, 88 million trees, over 300,000 farms. The sector generates around 40% of agricultural exports and provides a livelihood for almost a million people, directly or indirectly. A large-scale incursion of Xylella would be more than just a “sector tremor”: it would be a clash of national identity.

What to do now

- Locking the “frontiers of life”. Reinforce controls on phytosanitary passports and random audits of nurseries; target high-risk species and origins; curb the informal market in young plants. Use rapid LAMP/qPCR kits for field screening and reserve lab capacity for confirmation.

- Strengthen the “last mile”. Fund seasonal monitoring of vectors in and around orchards (roadsides, fallow land, hedges). Train “farmer sentinels” to recognize symptoms and report them via a standardized form, with feedback loops that build trust.

- Bridging the outreach gap. Co-design messages with cooperatives and women’s harvesting groups; pay for farmers’ training time; distribute SMS/WhatsApp alerts timed to vector phenology.

- Pre-activate compensation. Publish a clear protocol: when trees are uprooted, how soon payments are due, and what replanting options exist – so that early warning doesn’t feel like self-punishment.

- Repeat the emergency. Multiply inter-departmental exercises (ports, nurseries, labs, governorates) until roles are automated; capitalize on the lessons learned in Hammamet to plug weak spots.

Even if Tunisia holds the line, hotter, drier summers and more erratic rainfall will continue to favor vector dynamics and plant water stress. The country’s best defense is the one it has already begun to build, but faster, more equitably, closer to the plots. Protecting the olive tree is not nostalgia: it’s economic realism, climatic adaptation and cultural survival combined.

Spot it. Report it (for olive growers and nurserymen)

- First symptoms on olive trees: leaf scorch starting at the tips/edges, “roasted” edges with still-green tissue along the midrib; twig dieback; slow growth. (No single symptom is diagnostic – always take samples).

- Vectors to watch out for: scum leafhoppers (Aphrophoridae) on wild grasses in spring; adults move to trees as the herbaceous vegetation dries out. Avoid mowing wild host plants until most of the vectors have left them, to avoid mass flight to olive trees.

- In case of suspicion: record GPS coordinates; photograph several leaves/plants; isolate plant material; contact DGSV via regional services or the national contact point (IPPC). Do not move suspect plants off-site.

Copyright: FAO

Copyright © 2025 Blue Tunisia. All rights reserved

References:

- https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/plant-health-and-biosecurity/trade-plants-plant-products-non-eu-countries/declarations-non-eu_en?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- https://www.agritunisie.com/xylella-fastidiosa-une-menace-imminente-pour-les-oliviers-tunisiens/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/9563?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/xylella-fastidiosa-une-menace-pour-les-oliviers-et-des-centaines-de-plantes?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- https://www.iosfax.agrinet.tn/