The heroines of Tunisian shores: women clam diggers are facing an unprecedented environmental and socio-economic crisis. With clam stocks dwindling at an alarming rate, the authorities have suspended harvesting for the past three years. The figures are startling: a vertiginous drop from 1,547 tonnes in 2016 to just 44 tonnes in 2020. This reality plunges the women of this noble profession into a critical socio-economic situation, confronting them with colossal challenges.

Zarat, Gabès, May 2023

Clams in peril: Shoreline heroines face an uncertain horizon

Clam digging has always been at the heart of my life, ever since I was a child. I inherited this precious tradition from my mother and grandmother. But now I wonder if there are any clams left in the sea?

Khadija Nemri

Khadija Nemri, 51, a “Laggata” woman collector from Gabès for 30 years, describes the economic challenges facing women in this sector.

The weather in Zarat exudes a charm typical of southern Tunisia: a gentle breeze caressing the skin and sunshine illuminating the beach. However, that’s not enough to discourage the fisherwomen on foot, also known as “Laggata”. In Zarat, when the tide goes out at 11 a.m., many of these women gather on the beach. They look for the two small holes in the sediment that indicate the presence of clams, known locally as El Gafella. Draped in their traditional Mdhalla hats, wearing rubber boots and armed with a bucket and a sickle, known locally as “El Menjel”, they prepare for the assault on their quest.

However, a very different reality awaits them. “Are you aware that clam digging has been banned in these areas for the last three years?” the local authority’s surveillance officer firmly warns, constantly calling the women to order and forbidding them to collect anything.

Since 2016, the clam industry in Tunisia has been hit hard by a significant drop in national production. According to data from the Direction Générale de la Pêche et de l’Aquaculture (DGPA), clam stocks have fallen dramatically, from 1,547 tonnes in 2016 to just 44 tonnes in 2020. In coastal areas, these shellfish play an important socio-economic role. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), they represent a stable source of income and a livelihood for over 4,000 Tunisian women. Today, however, this category of fishery workers finds itself trapped between environmental and economic issues.

On Tunisia’s Mediterranean coast, only a few hours elapse between the first harvest of clams, their sale on the spot and their export, mainly to Europe. The Tunisian clam, renowned for its ease of tasting, is featured on restaurant menus, notably in Rome and Madrid, testifying to its gustatory success.

Yet, despite this geographical proximity between the two continents, a considerable gulf separates the Tunisian fisherwoman from the Italian restaurateur. While the former harvests these precious shellfish for just over 1 euro a kilo (or 3.2 Tunisian dinars), the latter earns 10 to 15 times more.

Tunisian clams: Between natural disaster and human action

Over the years, the precious fishery resources of the Tunisian Sea, once rich in octopus, shellfish, sea grasses and fish, have suffered considerable damage. Harmful practices such as illegal fishing and unregulated trawling are to blame. Unfortunately, traditional artisanal fishing, which played a crucial role in preserving marine biodiversity, is gradually disappearing. Tunisian waters also face another major problem: pollution. The offshore exploitation of hydrocarbons in the southern region and pollution from the chemical industry in the Gulf of Gabès are further aggravating the situation.

Chadlia Trabelsi, 51, a clam digger from Zarat, tells us about her experience of the harmful effects of this form of pollution.

During our collections, we are sometimes confronted with a disgusting smell emanating from the clams, particularly when the pollution from Ghanouch is making itself felt.

Chadlia Trabelsi

The deterioration of the marine ecosystem is a cause for concern, endangering not only marine species, but also the livelihoods of sea-dependent communities.

Najia El Ayedi, another female clam digger in Zarat, shares a deeply moving experience.

My husband, a fisherman by profession, sees every day the devastation caused by irresponsible trawling practices. He strongly advises against anyone going into this profession, least of all our own children.

Najia El Ayedi

The repercussions of this crisis are not sparing the “Laggata” community. The alarming decline in the clam population in the Gulf of Gabès, in southern Tunisia, particularly in Zarat, where production is gradually declining, is causing concern among scientists, fishing professionals and local authorities. Overexploitation, directly linked to a significant increase in fishing effort, is often identified as one of the main factors contributing to the deterioration of clam stocks in Tunisia.

Ines Houas Gharsallah, researcher and assistant professor at the INSTM’s fisheries science laboratory, stresses: “Any activity practiced in an anarchic manner, without regulation or monitoring, can only have a harmful impact on natural resources, and unfortunately this is the case for clams, where collecting persists even after it has been banned.”

Climate change: a clear threat to the disappearance of clams

Another threat facing the bivalve is climate change. The effects of this phenomenon are being felt suddenly and alarmingly in Gabès: a sudden rise in water temperature and rapid acidification of the sea, resulting from human activities in the vicinity of the region.

Ines Houas, highlighting the impact of overexploitation on the decline in clam stocks, in no way underestimates the importance of climate change in this decline. In her view, this environmental crisis is exerting additional pressure on coastal habitats, which are subject to incessant tidal fluctuations. These cumulative factors pose a serious threat to the future of clams.

In addition, professionals and scientists are keeping a close eye on water acidity levels, another threat to clams.

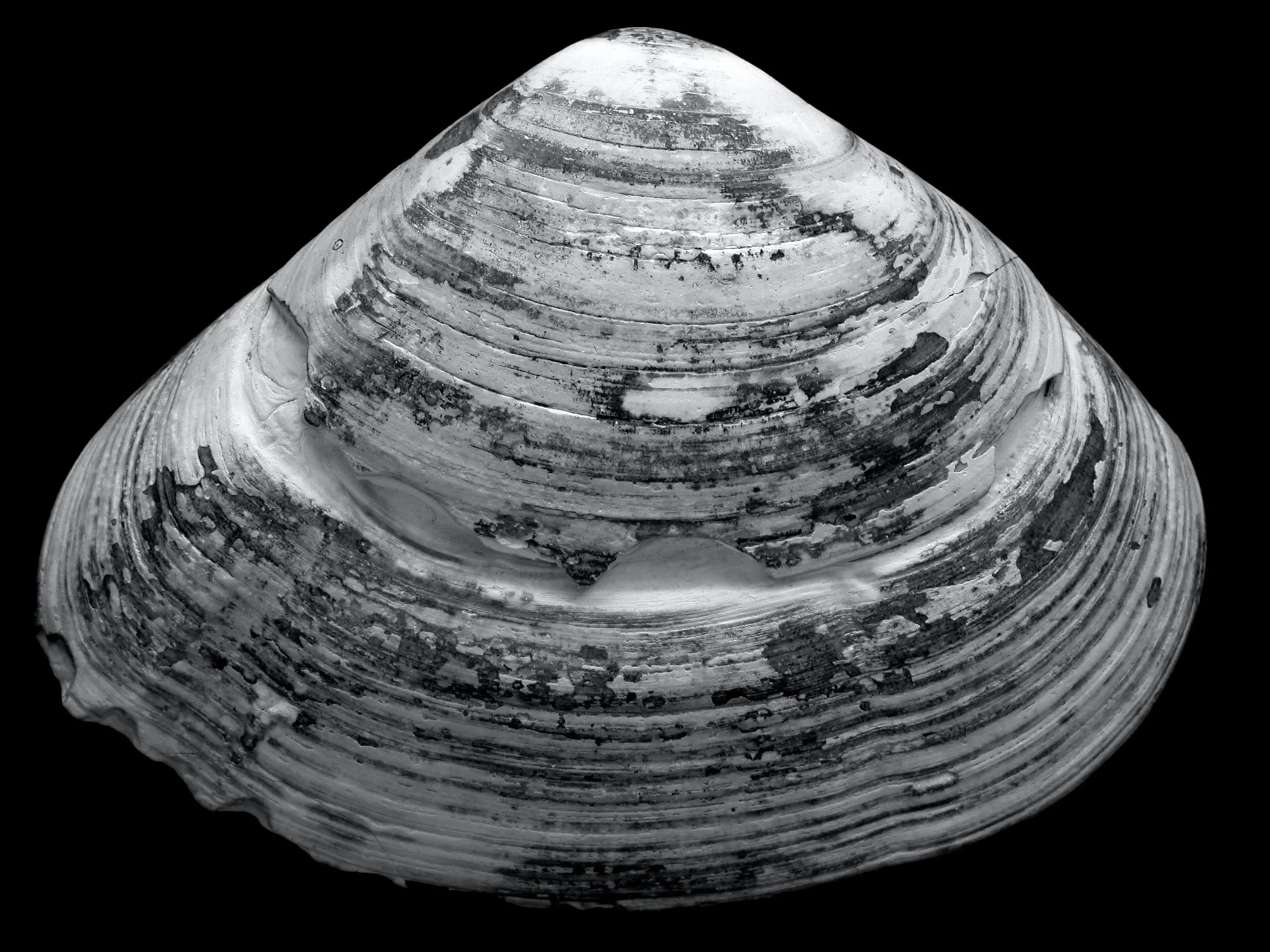

“The effects of climate change, such as rising temperatures and acidification of seawater, are having a considerable impact on clam resistance. High temperatures directly affect the survival of these marine organisms, while water quality plays a crucial role in the formation of their shells. Clams absorb elements from their aquatic environment to build their shells over time”, explains Ines Houas Gharsallah.

By absorbing a third of the world’s CO2 emissions, the oceans trigger a chemical reaction. The pH of the water decreases, causing a major disturbance known as “ocean acidification”. This phenomenon is lethal for molluscs such as clams, as it reduces the availability of the calcium molecules these bivalves need to build their shells.

The fragility of clam shells is an alarming fact confirmed by the women who collect them at Zarat in Gabès. Khadija Nemri, one of them, shares her observation:

Over the past ten years, when I’ve managed to collect a few specimens of clams, I’ve noticed that their shells are thin and break easily.

Khedija Nemri

Toxins in the sea: what clams tell us about the ecological state of the area

How aquatic organisms respond to climate change has become one of the most active areas of research. Scientists are striving to understand the repercussions of this phenomenon on marine resources, in a context where food security is at stake. A study carried out at Istanbul University’s Laboratory of Radioecology brings new advances to this field, using isotope techniques to analyze the consequences of climate change, particularly ocean acidification, on marine resources.

Increasing ocean acidity has significant effects on marine organisms, which are of major socio-economic importance. Using nuclear techniques, researchers have discovered that certain organisms absorb and accumulate more radio-nuclides or metals in response to ocean acidification. These elements slow the development of organisms or require more food for their survival.

The Istanbul University study, using radio-trackers, found that clams exposed to slightly acidified seawater absorbed twice as much cobalt as under balanced control conditions. In contrast, other marine organisms, such as oysters, show greater resilience.

These results show that ocean acidification poses a risk not only to clams, but also to consumers. Cobalt is a heavy metal that the human body needs in minute quantities, but which is toxic in high concentrations. This phenomenon can have even wider socio-economic repercussions on Mediterranean coastal populations, who depend on seafood both as a source of food and as a commodity for export to European countries.

An uncertain future: In search of alternatives for Laggata survival

Clam harvesting is subject to strict regulations laid down by the Ministry of Agriculture and Hydraulic Resources. Pursuant to law no. 94-13 of January 31, 1994, which sets the authorized period for clam harvesting as October 1 to May 15, the Ministry of Agriculture issued a decree on September 20, 1994 to govern this activity. This collection period has been carefully selected to preserve the reproduction phase of these marine animals and guarantee the sustainability of their population. However, the relevant authority reserves the right to modify the opening date of the campaign until November 15, taking into account bioclimatic particularities, requests from the profession and the results of scientific studies carried out on production sites.

But are women clam diggers really complying with all these rules?

The situation is complex and alarming. On the one hand, these women are exploited by unscrupulous middlemen who profit from their hard work. On the other, the authorities have issued strict bans on shellfish harvesting, plunging these women into a deep crisis. This worrying situation is exacerbated by the environmental, economic and social changes affecting Tunisian seas.

“Given that suppliers continue to encourage women to collect clams and pay them, and that they manage to cover their expenses and their family’s needs in this way, they’re not ready to give up the practice. If the decline of clams is real, why do others continue to profit from them? “asks Halima Souissi, a laggata woman from Kerkennah, expressing the concerns and dilemmas facing these women collectors.

Despite this complex and alarming situation, these women have become aware of the need to rely on their own resources and to work in compliance with laws and regulations in order to avoid prosecution. They have committed themselves to development projects aimed at strengthening the socio-economic capacities of vulnerable populations, with a view to finding lasting solutions to their dilemmas.

These include the NEMO KANTARA project, which focuses on the stabilization and socio-economic development of Tunisia’s coastal regions. This project has partnered with the Groupement de Développement Agricole et de la Pêche (GDPA) in Zarat, to provide an alternative to clam harvesting, which is in danger of running out. This initiative has facilitated the manufacture and design of metal traps for fishing blue crabs, providing an alternative activity for women collectors. Another project, FAIRE pour les femmes travailleuses dans l’Agriculture, supports the socio-economic empowerment of women working in agriculture and fishing in Tunisia. It also aims to retrain clam diggers in other sectors, such as agriculture and livestock breeding, where many women have already demonstrated their independence, initiative and leadership in their projects.

These initiatives highlight the need for enhanced monitoring to preserve this precious resource, as well as raising awareness among clam collectors and promoting sustainable practices. We are currently facing a race against time to ensure the long-term survival of these emblematic shellfish of our seas.

This article was developed in collaboration with the Earth Journalism Media Mediterranean Initiative.

Copyright © 2023 Blue Tunisia. All rights reserved

Sources:

- Haouas Gharsallah, I. H., Ugolini, R. U., Derbali, A. D., Djabou, H. D., Fezzani, S. F., & Jarboui, O. J. (2020). Clam fishery management plan. CIHEAM Bari and INSTM.

- INSTM. (2017). Final report of the FMM project “Enabling women to benefit more equally from agrifood value chains” implemented by the FAO.

- http://Ibn Chbili, A. I. (2016). Gender-sensitive value chain analysis of the clam industry in production areas G2 and S5. In FMM/GLO/103/MUL. Direction Générale de la Pêche et de l’Aquaculture and FAO. https://www.fao.org/fi/static-media/MeetingDocuments/BlueHope/secondmeeting/Value%20chain%20development/Etude%20chaine%20de%20valeur%20FMM%20%20%20%20Tunisie%20(1).pdf

- http://Danger at sea: what clam atoms can tell us about ocean acidification (2021, April). IAEA. https://www.iaea.org/fr/newscenter/news/danger-en-mer-ce-que-les-atomes-des-palourdes-nous-apprennent-sur-lacidification-des-oceans