22.3% is the alarming filling rate of dams in Tunisia, as of September 27, 2024, with a stock of 522 million cubic meters of water, down 13.5% on the same period in 2023, according to data from the National Observatory of Agriculture. Tunisia, faced with a serious drought situation, is seeing its reserves dwindle as a result of insufficient rainfall. This decrease reflects the worsening water crisis, accentuated by the climate crisis and exceptionally high temperatures in recent summers, leading to massive evaporation of water from dams and underlining the impact of climate change on the country.

In the face of this urgency, the adoption of methods adapted to climate change and efficient in the use of water resources is essential to strengthen the country’s resilience in the face of an increasingly alarming water and climate crisis. Among these solutions, the ancestral jessour technique, widely used in the arid regions of south-eastern Tunisia, stands out for its efficiency in water reclamation and could well be a key to the future.

Les jessour: What is it?

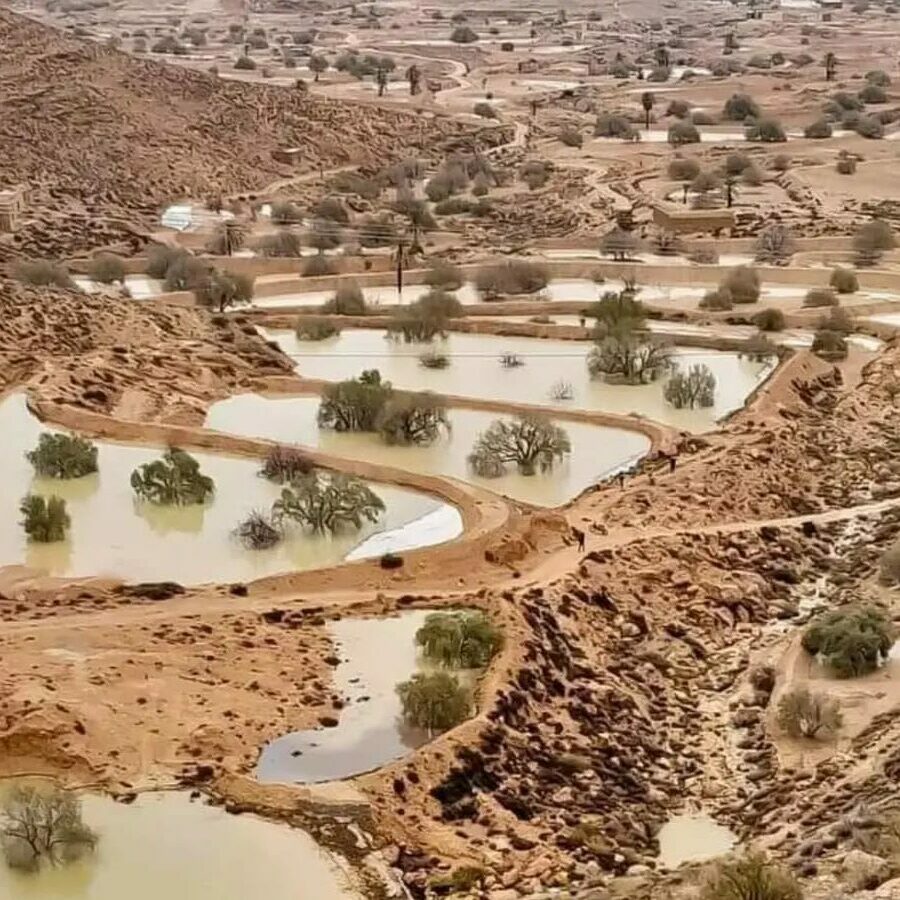

Jessour (plural of jesr) is an ancestral water and soil management technique developed over thousands of years on the Dahar plateau in southeastern Tunisia (the Matmata mountain range). It’s a system of traditional practices adapted to hilly terrain, allowing rainwater to be retained and limiting soil erosion.

This traditional engineering method captures and stores rainwater, maximizing its duration and usefulness for crops in areas with low rainfall. By enabling optimal water management, this method not only helps preserve crops but also mitigates the effects of prolonged drought.

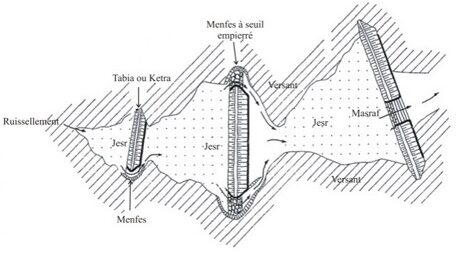

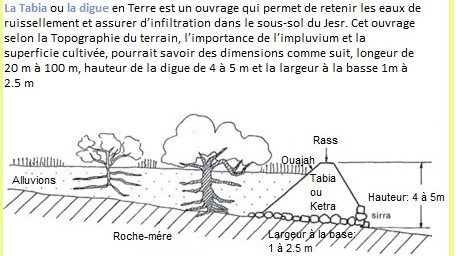

The jessour is an ingenious system made up of several elements. An impluvium(a sloping surface for rainwater runoff called a meskat) collects the water and directs it towards a flat cultivable plot(khlis). An earth dam, reinforced with stone blocks at the base(tabia or ketra), can be several dozen meters long, 4 to 5 meters high and 1 to 2.5 m wide. Its trapezoidal shape with a flat top maximizes water retention and, consequently, ensures prolonged soil moisture to support the crops grown.

Each tabia has a central weir(masref) or a lateral weir(manfes), which drains the overflow to the terraces below. The terrace fringe adjoining the tabia(mangaa) receives the maximum amount of water and remains moist for a long time, creating ideal conditions for agricultural crops (legumes: broad beans, lentils, peas and also barley, etc.).

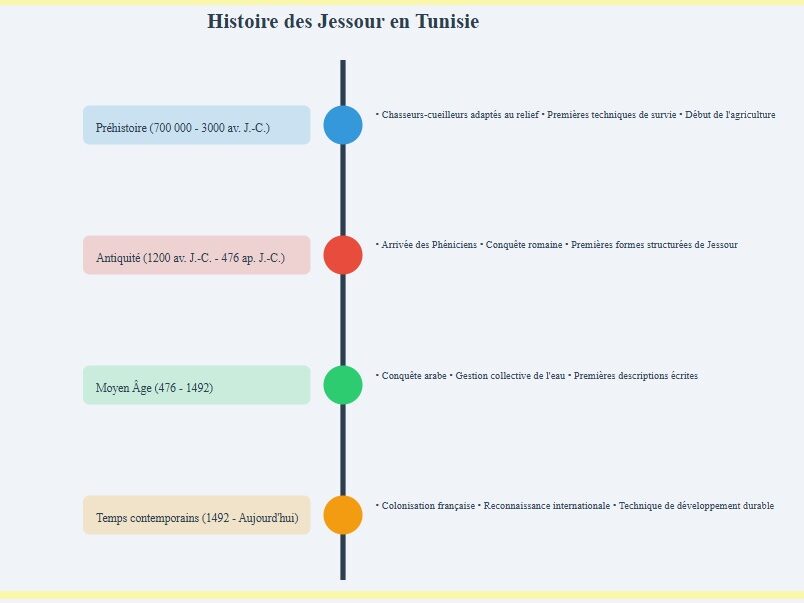

A thousand-year-old heritage rooted in history

Jessours are a testament to human ingenuity in the face of climatic challenges, particularly in the area of water management. Although the exact origin of this technique remains unclear, archaeological research suggests that these structures date back to late Antiquity, during the Roman Empire. However, earlier influences, notably Punic and indigenous, also contributed to their development. Some researchers argue that olive cultivation, introduced to Tunisia by the Phoenicians, played a key role in the emergence of this method. The olive tree, emblematic of the Mediterranean basin, found in the jessour an environment conducive to its growth thanks to the retention of water and sediments. The association between the arrival of olive trees and the emergence of jessour in the Dahar region could therefore shed light on the origin of this technique.

Further testimony to their historical importance can be found in the book القسمة وأصول الأرضين by Abu Abbas Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Bakr al-Farista’i al-Nafusi, published in the early 12th century. This work describes in detail the importance of the jessour in the social and economic organization of the communities of the Dahar plateau and Jebel Nafousa in Libya. It discusses strict rules for the maintenance of these agricultural structures and the management of water resources, underlining their fundamental role not only as agricultural tools, but also as key elements in the social fabric. The jessour encouraged cooperation between neighbors and ensured an equitable distribution of land. These principles, supported by a detailed system of laws, show just how essential collective land management was to the social and economic stability of the time. So, almost nine centuries earlier, these guardians of the water had already reached a form of maturity.

While some researchers attributed these structures to the Romans or Phoenicians, more recent studies, such as those by Pierre Trousset, a French historian and specialist in Mediterranean archaeology, reveal their profoundly indigenous character, probably dating from before the arrival of the Phoenicians. These hydraulic structures, adapted to the conditions of the Tunisian pre-desert, have evolved over time, integrating Eastern, Roman and local cultural influences. They embody ancestral know-how, passed down from generation to generation, designed to adapt to the extreme climatic realities of the region.

Efficient engineering for sustainable water and soil management

The Dahar, a vast, steep, arid region, is much more than a desert. Its rugged terrain and mountains have given rise to hydro-agricultural techniques that have adapted to extreme conditions. The jessour “are a heritage in their own right, rich in culture, history and environment”, says Tarek Ben Fraj, geographer-geomorphologist at the University of Sousse.

In the arid regions of south-east Tunisia, where annual rainfall fluctuates between 100 and 200 mm, every drop of water is precious. These ancestral hydro-agricultural structures offer a creative and sustainable solution for maximizing rainwater recovery while transforming steep, arid land into fertile spaces. A real bulwark against drought and soil degradation, these water guardians combine water efficiency, agricultural resilience and environmental impact.

“The purpose of the jessour is twofold: to capture and store as much runoff as possible, while retaining sediments to create fertile soil. Over time, this cultivable substrate can reach a thickness of 1 to 8 metres. Every time it rains, each jesr retains part of the water, while the surplus flows to the next structure downstream, thanks to an inventive system of weirs.

integrated into the tabias. These weirs (Masref or Manfes), generally located 30 cm above the plots, enable optimum water management between the different levels. Each jesr is also associated with a khlis cultivable plot, which benefits directly from the retained moisture and nutrients, guaranteeing sustainable agricultural productivity, even in arid conditions”, explains Ben Fraj According to Nourredine Ben Mouhamed, an expert in climate change and water. “a well-maintained jesr can retain up to 500 mm of water per year, i.e. annual rainfall is multiplied by a factor of 2.5, enabling the land to remain productive for almost two years or even longer”. This long-lasting retention ensures prolonged humidity that sustains crop life even in periods of prolonged drought.

Source : Tabias et jessour du Sud tunisien Agriculture dans les zones marginales et parade à l’érosion J. BONVALLOT

Indeed, the soil of a jesr, which can cover a cultivated area ranging from 1,000 m2 to 1 ha depending on the level of development and the aridity of the site, retains sufficient moisture to feed plants for several months, even years, without the need for additional water, since the loessic nature of the soil in jessours allows rapid infiltration of up to 25-65 mm/h.

These structures are designed to capture and reclaim runoff water from rare rainfall events, and consist of earthen dykes, sometimes reinforced with dry stone, erected in wadis to retain water and sediment transported by floods. The dykes, tabias, create temporary basins where water accumulates, allowing gradual infiltration into the soil.

Source : Tabias et jessour du Sud tunisien Agriculture dans les zones marginales et parade à l’érosion J. BONVALLOT

Jessour : a mainstay of rain-fed agriculture in southeastern Tunisia

Beyond their essential role in water management, jessours are at the heart of local agriculture. This ancestral concept, handed down from generation to generation, enables the inhabitants of arid regions to practice productive rain-fed agriculture, despite an often deficient water balance.

“We have inherited this technique from our ancestors, from father to son. All our farming is based on this system. In almost every family in the south-east, we ‘live by it’: we eat thanks to the jessour harvests, and we sell the surplus,” confides Selma Hadded, a farmer from Tamazret, a village around ten kilometers from Matmata in south-east Tunisia.

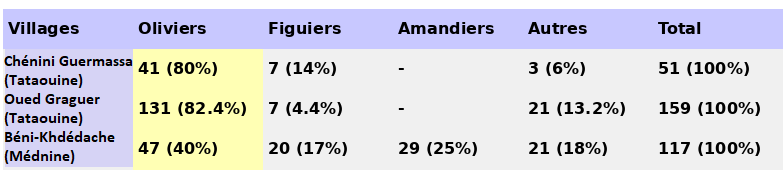

Thanks to this ancestral know-how, jessours make it possible to establish a production system based on rainwater agriculture, essential for the subsistence of local communities. “These small hydro-agricultural units enable farmers to harness run-off water and retain sediment, creating a fertile substrate that enriches the soil and generates remarkable agricultural yields, even in arid environments,” explains Nourredine Ben Mouhamed. The jessour also supports diversified agriculture, adapted to local constraints. Trees occupy a central place in this system, in particular olive trees, which represent the majority of trees, but also fig, almond and date palms. A well-developed olive tree in a jesr, for example, can produce up to 200 kg of fruit a year. “This technique has made it possible to practice arboriculture, particularly olive growing, which is the most predominant tree in this region. Thanks to the conservation of moisture in the soil of the plots, this deep storage allows the trees to survive, even during long periods of drought”, explains Tarek Ben Fraj.

Legumes, on the other hand, are grown in areas where water accumulates in greater quantities. “Our agriculture is mainly tree-based, with olive trees, date palms, fig trees and legumes. Trees can be planted anywhere in the jesr, but legumes are only sown in the mangaa area, where rainwater concentrates in front of the tabia,” says Selma Hadded.

Source: Tunisian weather and climate observatory facebook page

Despite the absence of artificial irrigation, the jessours enable us to maintain profitable, sustainable agriculture. “Every season, we obtain good harvests, specific and adapted to our land, without needing to irrigate our trees, and this is made possible by the rainwater and water reserves absorbed by the soil and plants in our jessours ,” she adds.

Despite the absence of artificial irrigation, the jessours enable us to maintain profitable and sustainable agriculture. Every season, we obtain good harvests, specific and adapted to our land, without needing to irrigate our trees, and this is made possible thanks to the rainwater and water reserves absorbed by the soil and plants in our jessours .Salma Haddad.

An ancestral design at the service of the ecosystem

In addition to their hydro-agricultural role, jessours are proving to be an innovative and resilient response to the environmental and climatic challenges facing south-eastern Tunisia. This multifunctional system, deeply rooted in local agricultural history, is proving to be an appropriate solution to water scarcity, soil erosion, desertification and the development of sustainable organic agriculture.

Jessour are a perfect example of adaptation to climate change. They store water deep underground, preserve soils, promote local biodiversity and consolidate agriculture in a difficult environment. Nourredine Ben Mouhamed

With climate change, marked by falling rainfall and rising temperatures, these structures remain an effective solution, “they enable rainwater to be stored, even in the event of irregular distribution, by creating underground reserves. These moisture reserves help to maintain agricultural productivity and mitigate the impacts of drought,” he adds.

These structures play a central role in preserving local ecosystems: by retaining runoff water and sediments, they limit water erosion while stabilizing soils, thus protecting farmland from degradation. Their impact extends beyond hydric soils: by binding wind-borne sediments, they also combat wind erosion, a critical issue in arid zones where winds rapidly degrade surrounding land.

In addition, this mechanism reinforces the vegetation cover, encouraging the growth of local plants, preserving biodiversity and maintaining the cycle of micro-organisms in the soil. This reinforcement of vegetation contributes not only to the fight against desertification, but also to the ecological balance of particularly vulnerable areas.

Their contribution doesn’t stop there: they support organic and conservation farming that respects the environment. Thanks to their design, they enable land to be cultivated without the use of pesticides or chemical fertilizers, thus preserving the balance of ecosystems. These practices guarantee healthy agricultural production, while ensuring natural soil regeneration and creating favorable microclimates for crops.

In short, jessour are fully in line with the objectives of the three conventions defined at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. “By stabilizing the soil and encouraging the growth of jessour vegetation, and thus keeping it hard and braking the advance of the desert, they contribute actively to the fight against desertification. At the same time, they strengthen the plant cover and support micro-organisms and biodiversity, preserving local ecosystems. These ancestral structures represent a resilient tool in the face of climate change and also play an essential role in adapting to this phenomenon, by creating sustainable underground moisture reserves capable of mitigating the impacts of prolonged drought”, explains Nourredine Ben Mouhamed.

Source: Aerial imagery study of gully erosion in the jessour

of southern Tunisia.

This ancestral system is an effective and sustainable response to today’s ecological crises. By making the most of water and preserving natural resources, jessour illustrate a holistic approach that combines agricultural resilience and respect for the environment in the face of climate upheaval.

An under-exploited heritage to be developed

In a global context marked by a growing climate crisis and increasingly acute water stress, Tunisia is one of the 25 countries most affected by this problem, according to the World Resources Institute. However, in the midst of this crisis, Tunisia could rediscover in its traditions effective solutions to today’s challenges. The jessour, the thousand-year-old structures of the Dahar, represent an ecological system capable of combining sustainable management of natural resources with adaptation to climate change.

The jessour are not simply a relic of the past; they are a source of inspiration for the future. Tarek Ben Fraj

Their ability to optimize water use, protect soils and support agriculture makes them an adaptable model for other regions facing similar challenges. “Although typical of the Dahar region, these designs could also be extended to other Tunisian regions, such as Gafsa, Kasserine, Sidi Bouzid or Kairouan, which have similar landforms and climates. These areas could greatly benefit from these ancestral structures,” adds Ben Fraj.

Despite their proven effectiveness, jessours are still under-exploited. By combining traditional know-how with developed water management techniques, such as stone pocket irrigation, it is possible to improve their performance. “This method is a water storage and underground irrigation technique based on the placement of several rows of stones at the bottom of a channel between the rows of trees. These pockets capture rainwater, reducing runoff and encouraging water infiltration into the soil. By retaining moisture, they enable crops to survive longer, even during droughts, while increasing profitability,” explains Sherif Zammouri, an environmental activist from Zammour, a village in south-eastern Tunisia some forty kilometers from Médenine.

To guarantee the durability of jessour structures, it is necessary to strike a balance between traditional techniques and modern innovations. According to the experts, preserving ancestral know-how while integrating appropriate solutions is essential to enhance the effectiveness of these structures. “Hand-built tabias are more resistant than those made with machines, which often weaken the structures. By combining manual skills with mechanical assistance, these structures can be both durable and profitable,” asserts Tarek Ben Fraj.

Copyright: facebook page Histoire de Gabès

Modernization of the jessour could be based on a standardized construction model, taking into account local morphometric features (relief, geology, topography). “We need to modernize while respecting our heritage. Such a model would make it possible to optimize jessour construction while preserving their effectiveness”, he recommends.

However, their upkeep remains a major challenge, and farmers need strategic support to build, maintain and develop this heritage. Although subsidies are offered by the Commissariats Régionaux de Développement Agricole (CRDA) as part of the Water and Soil Conservation (CES) program, these are insufficient. “Building a jesr requires a lot of work, as does maintaining it, but costs remain high and aid is limited”, stresses farmer Selma Hadded.

Other promising initiatives, such as the Destination Dahar project, the Dahar UNESCO Geopark, the Culinary Route of Tunisia and the Eco-tourism Circuit: Memory of the Earth, Sahara and Oases, are helping to promote and conserve the region’s geographical, natural, cultural and agricultural heritage. These projects support micro-projects and showcase local products from the jessour cultures, “However, these efforts remain insufficient, and to ensure the sustainability of this heritage, it is essential to mobilize more investment and strengthen coordination between stakeholders, including NGOs and the state,” insists Sherif Zammouri.

In addition, media interest in jessour could play a key role in its promotion. “Unfortunately, this technique remains little known outside southeast Tunisia, yet in the current context of water crisis and prolonged drought, it could be generalized to other regions. Raising media awareness would encourage more regions to adopt this ancestral method, capable of mitigating the effects of drought”, suggests Sherif Zammouri.

In a country with prolonged droughts and dwindling water resources, the jessour show that yesterday’s solutions can light up the future. Preserving them requires investment, recognition and collective commitment. By making the most of this age-old treasure, Tunisia can not only preserve its heritage, but also develop a sustainable development model to meet the challenges of water and climate.

This work was carried out in collaboration with the Tunisian section of the Union de la Presse Francophone.